Almadén’s Mining Park was inaugurated on January 6th, 2008.

The restoration of all the facilities and their becoming a museum, as well as the urban infrastructure for the Mining Park has meant the investment of more than 20 M€. A significant part of the restoration of these spaces has been carried out with FEDER’s financing. The recovery of the Bustamante Furnaces (17th century) which in 1992 were declared heritage of cultural interest, and of Charles IV’s gate, was directly made by the Instituto de Patrimonio Histórico Español, which is attached to the Culture Ministry.

The Mining Park's facilities, wells and buildings are the heart of Spanish sites on the ,

World Heritage List June 30

2012, under the name Heritage of Mercury. Almadén and Idrija

The history of the mines of Almadén is as lengthy and rich as their production: from the 3rd century BC to present day, there has been uninterrupted mercury mining activity in the district of Almadén, with significant historical events that have been associated with the mines.

Sisapo or Sisalone, the name by which Almadén was formerly known, is Celtic for "cave from which metals are extracted". The historian Theophrastus, a pupil and friend of Aristotle, wrote that the hard cinnabar from Spain was highly valued. Both the Romans and the Arabs exploited the mine to extract cinnabar. This mineral, which was of a reddish colour, was used for painting and for dyeing.

In Roman times Almadén must have been considered as a rather important town, since it was also the location of a mint. A good number of Roman ‘aces’ (copper coins) have been found with the inscription SAESAPO.

The Arabs exploited the mines between the 8th and 13th centuries. Many Spanish terms used in the mining of mercury come from Arabic: almadén (from the Arabic al-ma 'daniy 'yun, "the mine" or "the mineral"), aludel, azogue, alarife. The so-called xabecas furnaces, which were used up to the end of the 16th century, also date from this period. In the 12th century, the mine had a depth of around 450 m and employed more than 1000 miners. Mercury was used by alchemists and doctors to prepare medicines and as decoration.

In the mid-13th century, Almadén was reconquered by the Christians and the mines were given to the Order of Calatrava, which leased them to Catalan and Genovese businessmen.

The mines continue to be leased to private businessmen during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. In 1523, the perpetual administration of the assets of the orders was transferred to the Spanish crown. The products commercialised during these centuries were vermilion, quicksilver and corrosive sublimate. The latter was made from quicksilver and used to tan leather.

From the 16th century onwards, mercury became an asset of great value thanks to its use in the amalgamation of the gold and silver that came from America.

Almadén became an important industrial and mining centre and contributed to the exploitation of the wealth that was brought from the new continent.

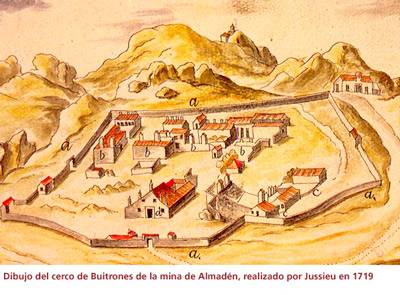

During the 16th and 17th centuries the mines were leased to the German Függer bankers (Fúcares, as they were known locally) to pay the loans given to Charles I to cover the costs of his coronation. This family of bankers, known as the German White House, brought many technical and organisational innovations to Almadén. The first of these innovations included the reverberation furnaces or "buitrones".

Most of the quicksilver produced was sent to Seville, from where it was shipped to America. It was so important for the Spanish economy in America that all the shipments of goods to the continent were adjusted to its production and, therefore, to the changes in the production levels of the mines at Almadén and its loading in Seville. Special ships were built designed to transport mercury, including the Tolosa, a ship of 1500 tonnes, and the Guadalupe, of 1000 tonnes.

From the 17th century , the production of the mines fell as a result of the depletion of the mineral in the known exploitations and because work was carried out in poor conditions. During this period, the mine saw its greatest tragedy: a fire that began in January 1755 and continued for more than two years, causing the death of many people.

During the reign of Charles III, various German managers from the Freiburg School (in Saxony) were appointed to modernise the techniques used in the mines and the mining school was founded in Almaden in 1777.

During the half-century under German managers and under the first Spanish successor, Diego de Larrañaga (trained at the mining school itself), significant innovations were made in the mining techniques. At the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the mining activity at Almadén underwent significant growth.

At the beginning of the 19th century the critical situation of public finances meant that the mines had to be mortgaged and the monopoly of mercury sales was given to the firm of Iñigo Espeleta, from Bordeaux, in 1833. In 1835, the quicksilver auction was awarded to the firm Rothschild.

In 1916 a special body was created to manage the mines. This body was known as, the Board, and it introduced improved mining techniques. After the Spanish Civil War, the mines reached record production levels in 1941 with 82,000 jars of mercury, partially conditioned by the use of prisoners as workers in the mine (the so-called forced labour gallery was reopened). From the year 1972, the world mercury market fell with the deep economic recession.

In 1982 the company Minas de Almadén y Arrayanes, S.A., S.M.E., was incorporated with capital that belonged entirely to the State through the General Department of Heritage.Since then, the company has been diversified significantly.

Since May 2001 , Minas de Almadén has been part of Sociedad Estatal de Participaciones Industriales. (SEPI).